Review of On-site

Wastewater Bylaws

Findings report

April 2018

2

Table of Contents

Table of Contents............................................................................................................................ 2

1 Summary of key findings ......................................................................................................... 3

2 Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 4

2.1 Purpose of the report ........................................................................................................ 4

2.2 Key questions ................................................................................................................... 4

2.3 Why review now ................................................................................................................ 4

2.4 Scope ............................................................................................................................... 5

2.5 Methodology ..................................................................................................................... 6

3 What currently governs OSWW management? ....................................................................... 6

3.1 National legislation regulating OSWW systems ................................................................. 7

3.2 The Auckland Unitary Plan................................................................................................ 8

3.3 OSWW legacy bylaws and Waitakere targeted rate .......................................................... 9

4 Are the issues the bylaws set out to address still evident? .................................................... 10

4.1 Purpose of the legacy OSWW bylaws ............................................................................. 10

4.2 Failing OSWW systems are contaminating waterways .................................................... 10

4.3 Call centre complaints and queries identify OSWW failure .............................................. 12

5 Are the bylaws still the most appropriate means for managing OSWW systems? ................. 13

5.1 Do the bylaws provide extra regulation than the Auckland Unitary Plan and legislation? 13

5.2 Do the bylaws provide greater enforcement power than existing legislation? .................. 14

5.3 Do council’s OSWW stakeholders identify any additional issues a bylaw could address?16

Key findings from Auckland Unitary Plan ................................................................................... 16

Key findings from local board engagement ............................................................................... 17

Key findings from interviews with enforcement officers ............................................................. 19

Key findings from Waiheke’s Compliance Monitoring Officer ..................................................... 21

6 Statutory review findings and conclusion ............................................................................... 23

7 Appendix ............................................................................................................................... 24

7.1 Estimate of OSWW location and scale ............................................................................ 24

7.2 Local board views table .................................................................................................. 26

7.3 Council enforcement officer views table .......................................................................... 29

7.4 OSWW bylaw provisions compared to Resource Management Act 1991, Building Act

2004 and Health Act 1956 ......................................................................................................... 33

3

1 Summary of key findings

The legacy on-site wastewater bylaws were intended to be replaced by the Auckland Unitary

Plan

• The Governing Body renewed the legacy on-site wastewater (OSWW) bylaws in 2015, so there

would be no regulatory gap until relevant provisions in the Auckland Unitary Plan became

operative.

• The legacy OSWW bylaws are now redundant as the operational Auckland Unitary Plan is

council’s guiding regulation for on-site wastewater management.

The issues the legacy on-site wastewater bylaws set out to address are still evident

• On-site wastewater systems are still an issue as evidenced by:

o human-sourced E. coli contamination across the region’s waterways

o customer calls to council identifying OSWW system malfunctions.

The legacy on-site wastewater bylaws are not needed

The Auckland Unitary Plan replaces the need for the legacy on-site wastewater bylaws. Further

evidence and reasoning are detailed in the four points below.

1. The legacy on-site wastewater bylaws do not provide additional regulation

• The legacy bylaws only provide an additional stipulation of requiring OSWW users to send in

their maintenance records proactively to council or when asked.

• The Auckland Unitary Plan already regulates record keeping by requiring OSWW maintenance

records to be kept on site for inspection by council’s officers.

• Proactive record keeping is achievable through building relationships with OSWW service

providers and effectively communicating responsibilities to OSWW users.

2. Existing legislation has greater enforcement power than the bylaws

• Current legislation provides more options for enforcement including the ability to issue on-spot

fines, serve abatement notices and issue large fines on conviction.

3. Engagement with council’s OSWW stakeholders revealed no need for bylaws

• Key findings from engagement included:

o current rules and regulations need to be simplified and communicated to OSWW users

o council needs a central database of OSWW systems and increased environmental

monitoring

o council should consider incentives as some owners cannot afford to maintain their OSWW

systems

o council should increase relationship building with pump out contractors to alert council to

impending OSWW issues and failures

o building relationships with OSWW operators and maintenance providers is crucial to an

effective maintenance reporting scheme. The bylaw assists, but it is not required for having

records sent to council.

4. The Auckland Unitary Plan is the appropriate means for addressing OSWW management

• If changes to regulation are needed, they should be administered through a plan change of the

Auckland Unitary Plan OSWW provisions instead of a bylaw.

Review of On-site Wastewater Bylaws

4

2 Introduction

2.1 Purpose of the report

This report presents findings from the review of Auckland Council’s legacy bylaws for on-site

wastewater (OSWW) management. The current legacy OSWW bylaws include:

• North Shore City Bylaw 2000

• Rodney District Council 1998

• Waiheke Wastewater 2008

• Papakura District Council Wastewater Bylaw 2008

Auckland Council (council) has a statutory responsibility under the Local Government Act 2002 to

review these bylaws by 31 October 2020.

2.2 Key questions

To meet council’s statutory review requirements under section 160(1) of the Local Government Act

2002, the bylaws must be determined as the most appropriate way of addressing the perceived

problem. To identify this requirement, the review asked the following key questions:

• What plans and legislation currently regulate OSWW management?

• Are the issues the OSWW bylaws set out to address still evident?

• Are the bylaws still the most appropriate means for managing on-site wastewater systems?

o Do the bylaws provide extra regulation compared to existing legislation?

o Do the bylaws provide greater enforcement power than existing legislation?

o Do council’s OSWW stakeholders identify additional issues a bylaw could address?

2.3 Why review now

2.3.1 Legacy OSWW bylaws were intended to be replaced by Auckland Unitary

Plan provisions

In October 2015 the Governing Body

1

confirmed the four legacy OSWW bylaws would remain in

effect until 31 October 2020, at which time they would be automatically revoked.

The Governing Body’s decision was taken under the recommendation from the Regulatory and

Bylaws Committee

2

in July 2015 to preserve status quo (keep the bylaws) until the relevant

provisions of the Proposed Auckland Unitary Plan became operative.

1

Governing Body, 29 October 2015, Resolution number GB/2015/112

2

Regulatory and Bylaws Committee, 08 July 2015, Resolution number RBC/2015/23

5

The Auckland Unitary Plan OSWW regulations became operational in September 2016. Section

20A of the Resource Management Act 1991 gave OSWW users six months to comply with the new

Unitary Plan standards or to obtain a resource consent. With the Auckland Unitary Plan provisions

now applying to all OSWW systems, the legacy bylaws could be reviewed for redundancy.

2.3.2 OSWW bylaw review aligns with Healthy Water’s OSWW management review

Auckland Council’s Environment, Climate Change and Natural Heritage Committee passed a

resolution

3

in March 2016 noting a cross-council project team would develop options to better

manage privately-owned OSWW systems. The council unit, Healthy Waters, is leading this project

and the bylaws unit is part of the project team. The results from the legacy OSWW bylaw review

will provide insights to help Healthy Waters develop options for OSWW management.

2.4 Scope

The review will include:

• the nature and extent of issues associated with inadequate OSWW management in

Auckland

• the effectiveness of the legacy OSWW bylaws in addressing these issues

• whether a new bylaw is necessary to address these issues or whether we already have

sufficient tools available (such as in the Resource Management Act 1991 and Unitary Plan).

2.4.1 Out of scope

The review will not include:

• water pollution issues associated with the reticulated wastewater system managed by

Watercare Services Limited, including:

o wastewater overflows from Auckland’s reticulated wastewater network, particularly

from the older combined stormwater/sewer system

o wastewater issues regulated by the Water Supply and Wastewater Network Bylaw

2015

o properties which are on Watercare’s reticulated network and therefore do not use an

OSWW system.

• regulating other sources of water pollution, such as stormwater, farming activities and

industry

• specific proposals about how to fund OSWW maintenance and upgrades.

3

RES ENV/2016/7

Review of On-site Wastewater Bylaws

6

2.5 Methodology

Various research and engagement methods were used to gain insight on the key questions.

Research: Desktop research was conducted on the existing plans and legislation for OSWW

management, including stipulations in the Resource Management Act 1991, Unitary Plan, Local

Government Act 2002, Building Act 2004, and Health Act 1956.

This research also drew on information provided by Healthy Waters on the nature of OSWW

system failure and the scale of the problem through environmental monitoring from the Safeswim

Programme and previous water studies.

Stakeholder engagement: Written communications and meetings were conducted with council

staff to seek input on the regulatory framework, how it works internally and if additional regulation

is required. Interviews were held with council staff from Auckland Unitary Plan, Licensing &

Regulatory Compliance, Healthy Waters, Resource Consents, Building Consents, Engineering and

Technical Services and Regulatory Litigation Services.

Local Board workshops: All local boards were invited to engage and provide feedback on the

issue. Informal workshops were held with six local boards who were presented with the current

regulatory framework and asked questions regarding known issues and whether additional

enforcement powers are needed.

Analysis of past OSWW bylaw reviews: The legacy bylaws were reviewed in 2014/2015 by the

then Planning Policies and Bylaws unit, and the results of those reviews were considered.

3 What currently governs OSWW management?

Auckland’s OSWW systems are governed by the following plans and legislation:

Regional plan and legislation

Legacy OSWW bylaws

• Auckland Unitary Plan (live 2016)

• North Shore City Bylaw 2000

• Rodney District Council 1998

• Waiheke Wastewater 2008

• Papakura District Council Wastewater

Bylaw 2008

• Resource Management Act 1991

• Building Act 2004

• Health Act 1956

• Local Government Act 2002 (bylaws)

7

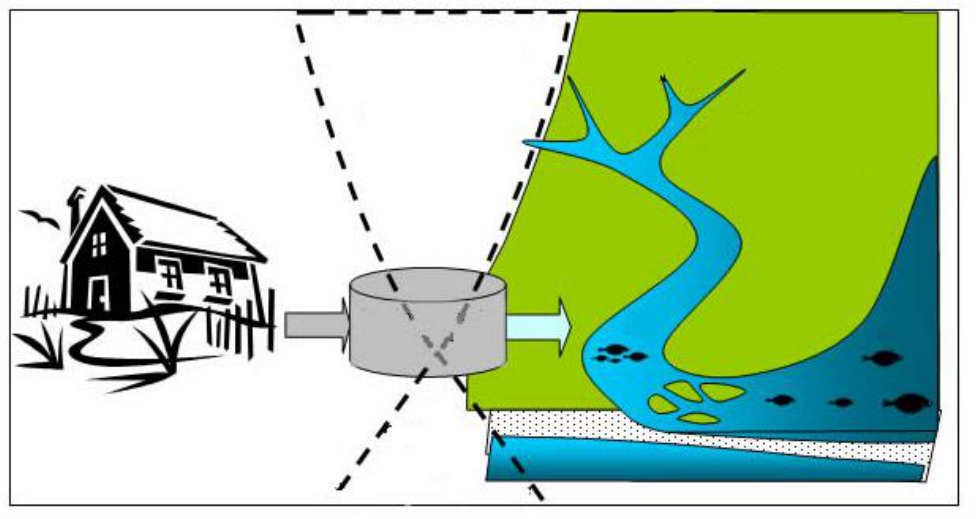

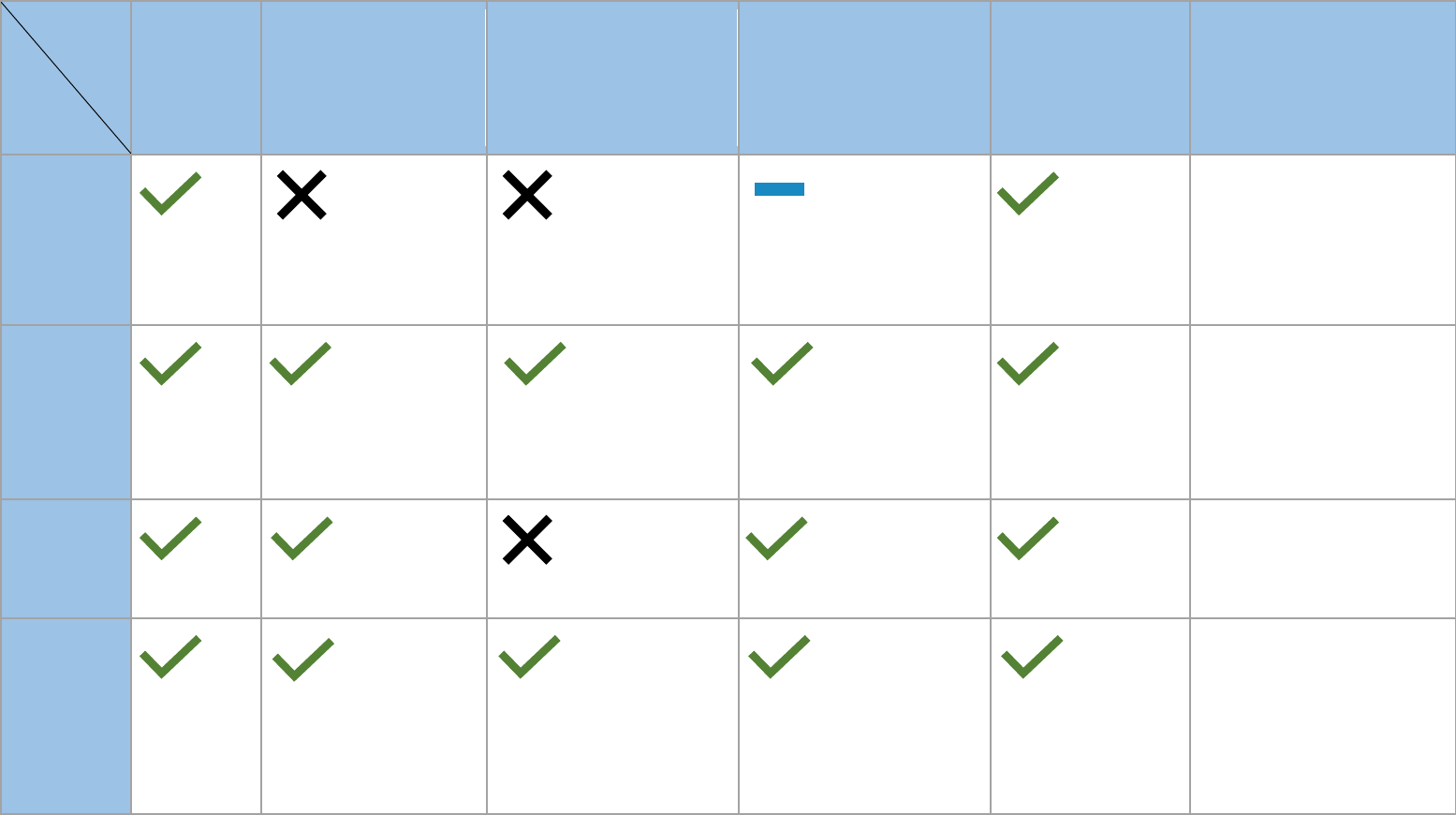

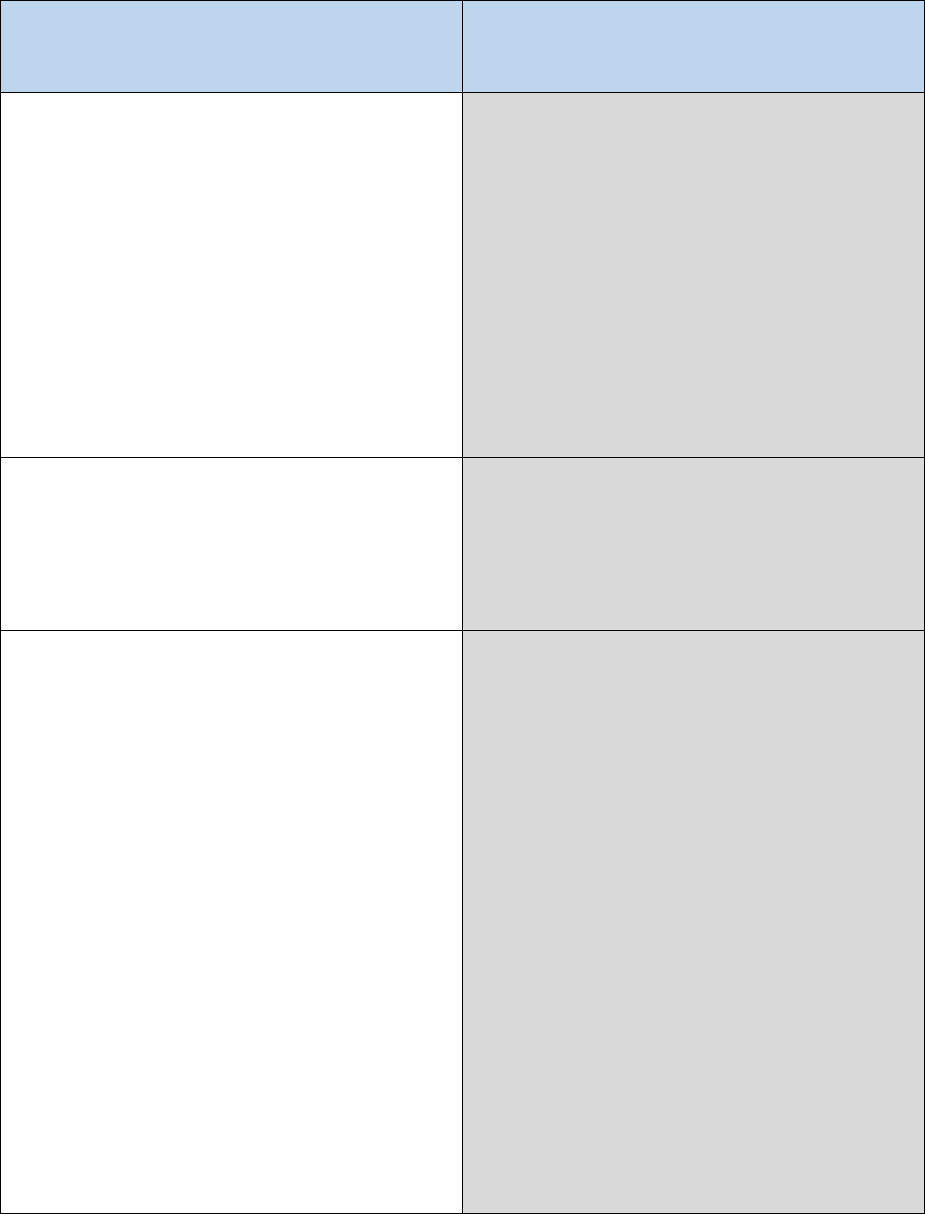

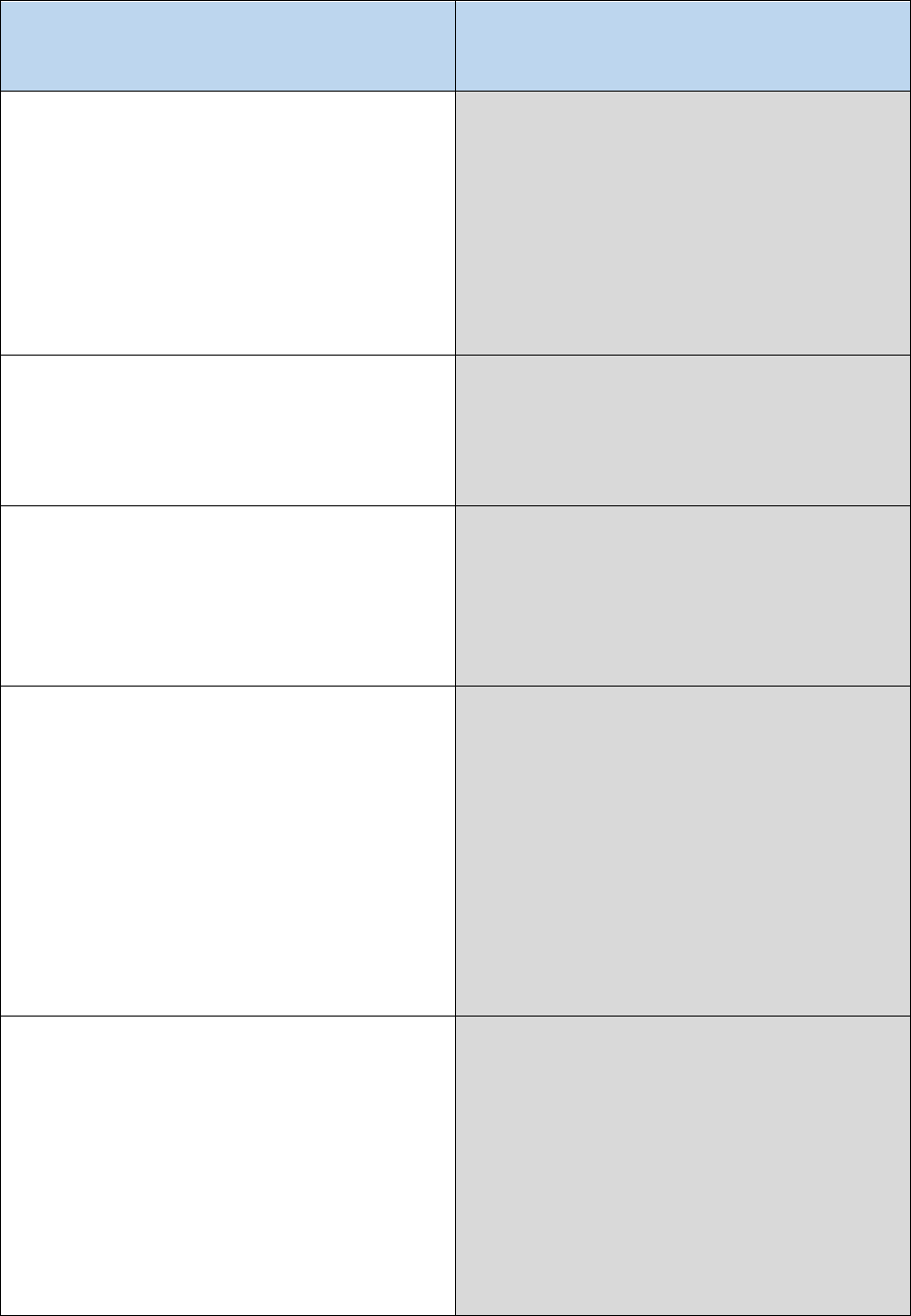

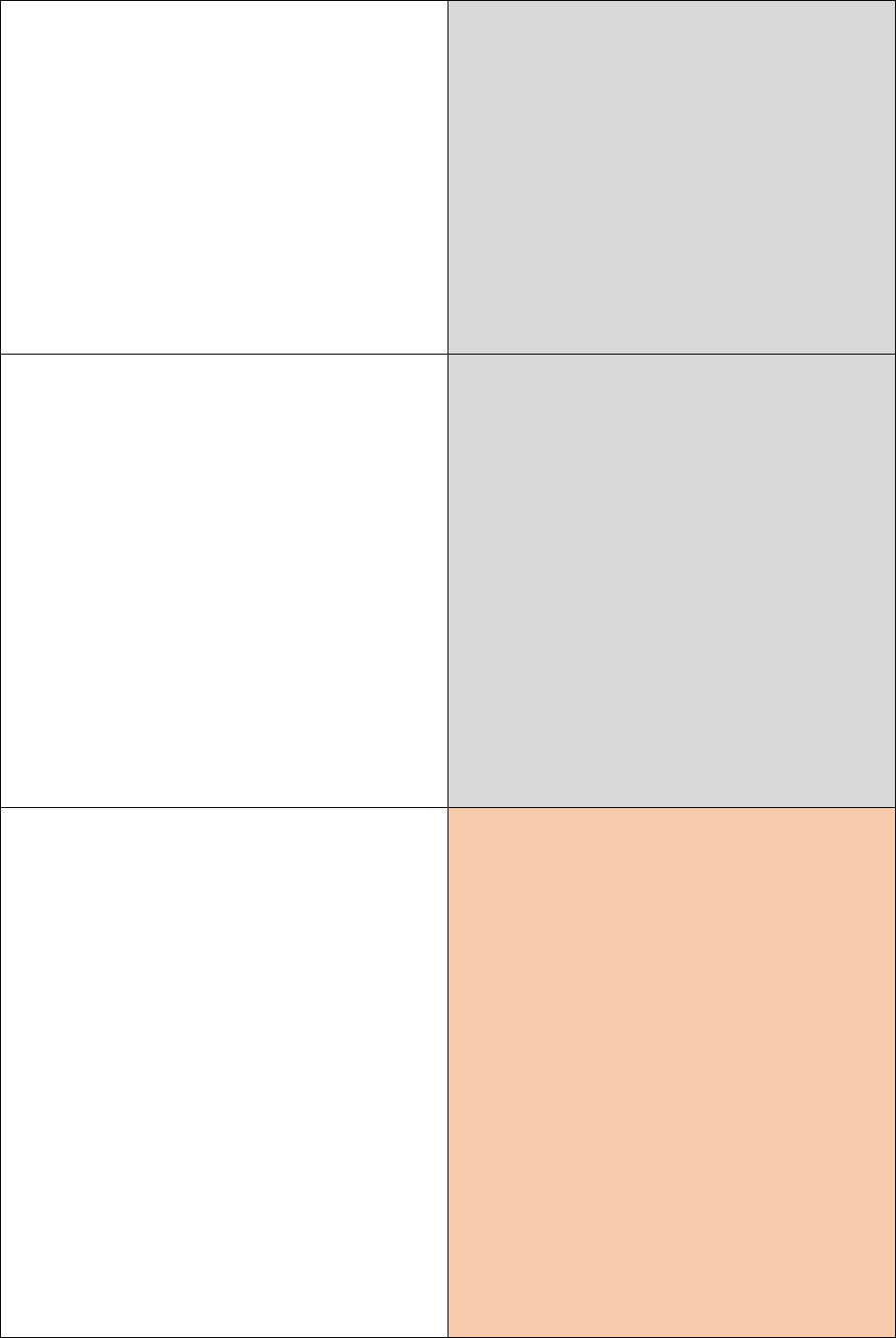

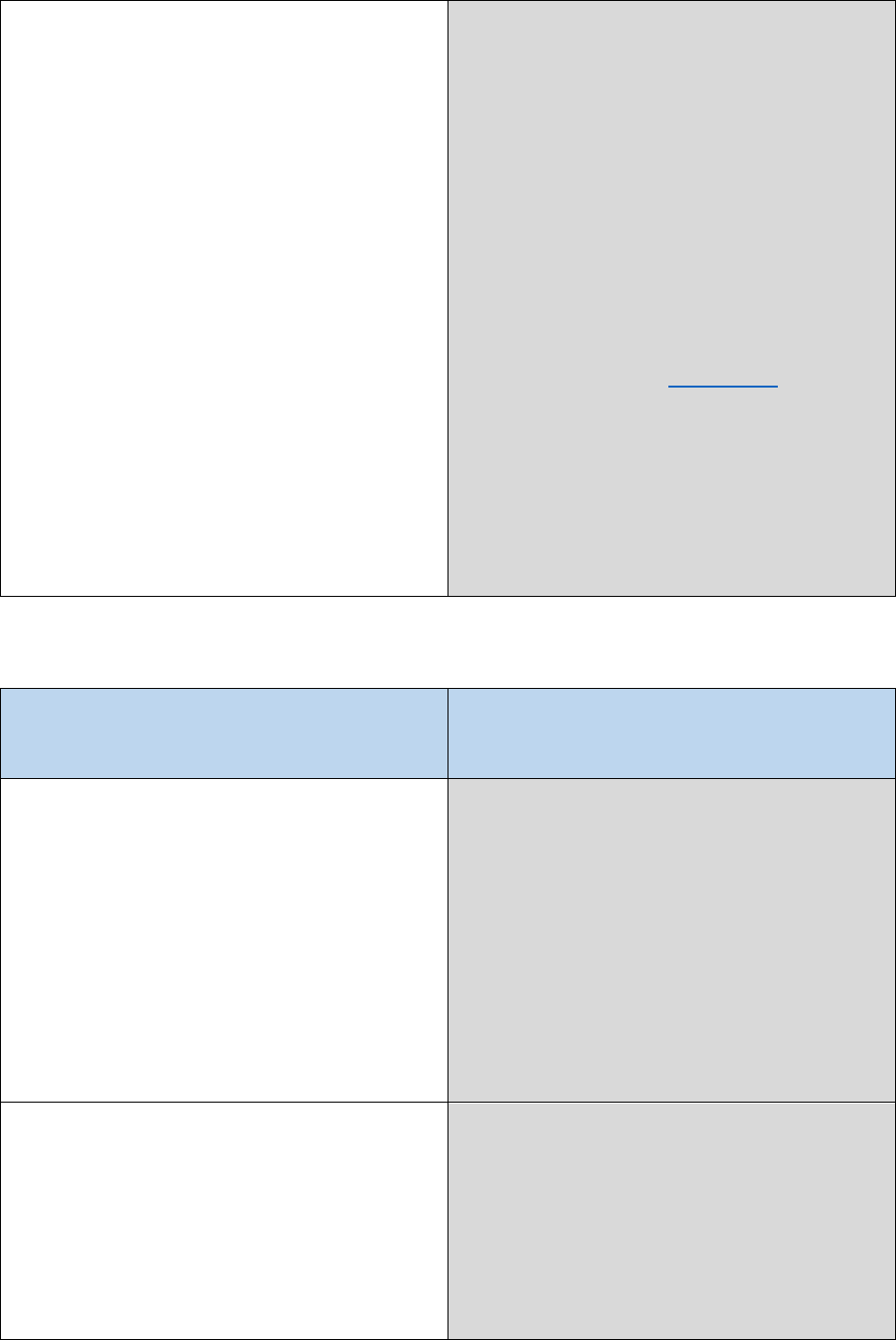

3.1 National legislation regulating OSWW systems

National legislation for regulating OSWW systems includes the Building Act 2004, Health Act 1956

and Resource Management Act 1991. These Acts work in tandem to regulate different aspects of

OSWW management as demonstrated below in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Summary of the national legislation for OSWW management

3.1.1 Building Act 2004

The Building Act 2004 classifies OSWW systems as a building which must obtain consent. It must

be designed and installed properly and operate in a safe and sanitary manner. Administered by the

council’s building consents and compliance teams, Section G13 (Foul Water) of the Building Code

specifically sets out the requirements for on-site wastewater systems’ design and construction.

Technical Publication 58 On-site Wastewater Systems: Design and Management Manual 2004

(TP58) provides additional guidance for the design and maintenance of on-site treatment and

disposal systems for domestic wastewater. TP58 is used as the basis for the assessment and

approval of building consents. It is currently being reviewed with an updated Guidance Document

(GD06) to be issued shortly.

3.1.2 Health Act 1956

The Health Act 1956 dictates that all dwellings must have suitable appliances for disposing of

wastewater in a sanitary manner. This regulation means that if a dwelling has no sewer access

available, it is then required to treat wastewater on-site. The Health Act 1956 goes on to regulate

septic tank desludging and sludge disposal and focusses on improving, promoting and protecting

public health. The Health Act 1956 allows territorial authorities to issue cleansing and closure

orders or require repairs if residential facilities, including OSWW systems, are insanitary.

Source: Ministry for the Environment, July 2008, Proposed National Environmental Standard for On-site

Wastewater Systems

Building Act 2004

Building inspectors,

territorial authorities

Building Code, design and

installation of system

Health Act 1956

Environmental health

officers

Public health

nuisance

Local

Government

Act 2002

Bylaws

Resource Management Act 1991

Ministry for the

Environment, regional

councils, regional plan rules

Receiving

environment,

council officers,

investigation

of pollution

Groundwater

Rivers

Coast

On-site wastewater

system

Review of On-site Wastewater Bylaws

8

3.1.3 Resource Management Act 1991

The Resource Management Act 1991 focusses on the health of the environment and gives power

to the Unitary Plan to regulate permitted standards regarding flow rate, technical design,

management and reducing adverse effects on the environment. Section 15 of the Resource

Management Act 1991 prohibits anyone from discharging contaminants into water or onto land in

circumstances which may result in that contaminant entering water, unless the discharge is

expressly allowed by a rule in a regional plan.

3.2 The Auckland Unitary Plan

The Auckland Unitary Plan prescribes permitted standards for discharging treated domestic

wastewater onto or into land via a land application disposal system.

Under the provisions of the Auckland Unitary Plan, the majority of OSWW devices are considered

permitted activities. Along with Auckland Unitary Plan key standards, if the flow rate is less than

2m

3

and the ratio of site area to discharge volume is greater than 1.5m

2

per litre a day, the OSWW

system is permitted. As such, only about 2,000 of the estimated 50,000-60,000 devices in the

region are not permitted and have resource consents.

Auckland Unitary Plan key standards for all on-site wastewater systems include:

• no significant adverse effects on public health, environmental health or Mana Whenua

• regular maintenance by a suitably qualified OSWW provider in accordance to:

o Technical Publication 58 On-site Wastewater Systems: Design and Management

Manual 2004 (TP58)

o the manufacture’s recommendations

o or service provider’s recommendations.

• septic tank inspections at least every three years and advanced treatments inspections every

six months

• records of each maintenance action must be retained and made available on site for inspection

by the council.

9

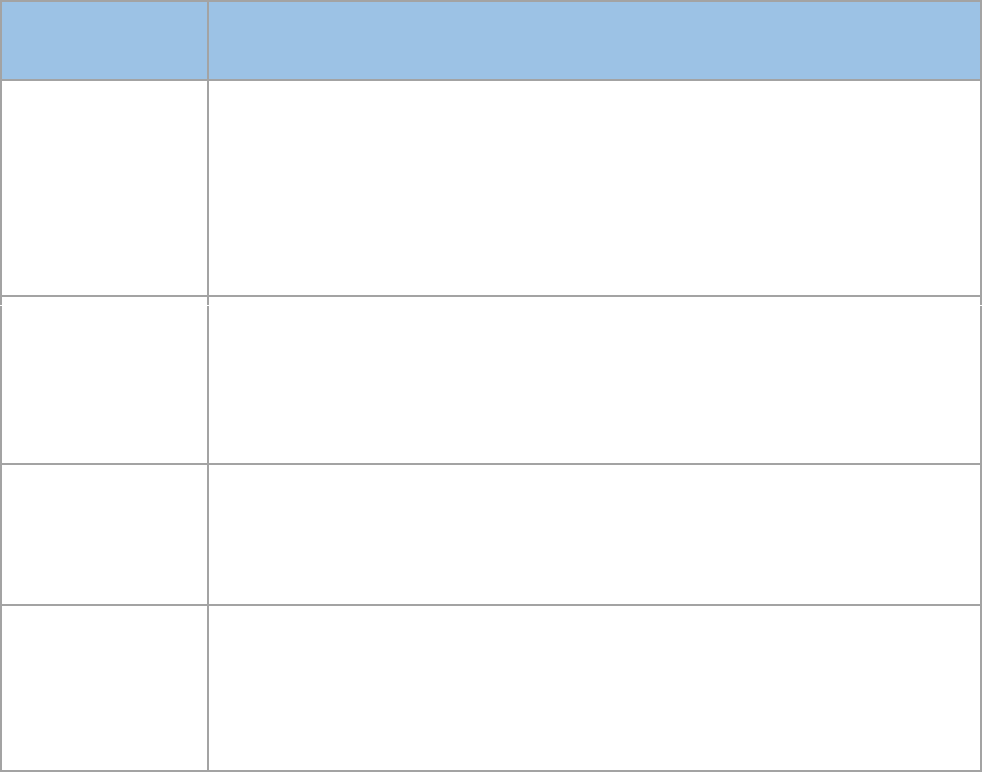

3.3 OSWW legacy bylaws and Waitakere targeted rate

The legacy bylaws seek to ensure septic tanks and domestic wastewater treatment systems are

installed and maintained in a manner which prevents the failure of the system. A summary is

provided below in Table 1. For a complete breakdown of the legacy bylaws see Appendix 7.4.

Table 1 - Summary of legacy OSWW bylaws

3.3.1 Waitakere pump-out targeted rate

Although not a bylaw, approximately 4,400 OSWW systems in the former Waitakere City Council

non-urban area, now mainly the Waitakere Ranges Local Board and parts of Henderson-Massey

Local Board, have their systems pumped out every three years by council. Costs are recovered at

a targeted rate of $185.13 as of February 2016. A high-level performance assessment is carried

out as part of the pump out process and property owners are notified of any faults.

Legacy OSWW

bylaw

Summary

North Shore City

2000

Stipulates:

• wastewater must be treated and disposed on-site if no sewer access

available

• OSWW systems shall be operated and maintained in accordance with

TP58

• where there is evidence of system failure or no maintenance contract in

place, the owner must remedy at their expense.

Papakura District

Council 2008

Stipulates:

• building consent procedures must be followed in accordance to TP58

• pump-outs must occur every three years with records sent to council

• officers have right of inspection

• breaches to the bylaw must be remedied at owner’s cost.

Rodney District

Council 2008

Stipulates:

• maintenance records must be sent to council when requested

• officers can serve written notice if an OSWW system fails

• officers can take appropriate remedial steps at the cost of the occupier.

Waiheke 2008

Stipulates:

• officers have right to necessary inspections

• sufficient detail must be provided with a building consent

• systems must be pumped out every three years with records proactively

sent to council.

Review of On-site Wastewater Bylaws

10

4 Are the issues the bylaws set out to address still

evident?

4.1 Purpose of the legacy OSWW bylaws

Council does not currently provide a reticulated wastewater system to everyone in Auckland. Many

of Auckland’s property owners in rural and coastal areas without access (est. 50,000-60,000

households

4

) must provide and manage their own OSWW systems.

The legacy bylaws seek to ensure septic tanks and domestic wastewater treatment systems are

installed and maintained in a manner which prevents the failure of the system.

4.2 Failing OSWW systems are contaminating waterways

OSWW systems are known to be failing from evidence of high levels of Escherichia coli (E. coli)

readings across the region’s waterways. DNA testing has identified human excrement to be a

cause. The resulting contamination poses significant public health risks and negatively impacts on

the ecological health of waterbodies and aquatic life in affected areas.

Auckland Council’s Safeswim Monitoring Programme determines the bacteriological water quality

of recreational water across the region during summer. The 2013/2014 Safeswim Summary Report

identified unsuitable levels of E. coli for swimming in some of Auckland’s streams and beaches.

4

See Appendix 7.1 for estimate methodology

Key findings

• The legacy OSWW bylaws seek to prevent the failure of OSWW systems.

• Failing OSWW systems are still an issue as evidenced by:

o human-sourced E. coli contamination in waterways

o customer calls to council identifying OSWW system leaks, overflows, bad smells and

lack of maintenance.

11

Exceedances frequently occurred at the following lagoons and beaches in 2013/14:

• Piha South Lagoon

• Piha North Lagoon

• Bethells Lagoon

• Karekare Lagoon

• Huia Beach

• Wood Bay Beach

• Titirangi Beach

• French Bay

• Laingholm Beach

• Te Atatu Beach

• Christmas Beach

Contamination is still as issue as the 2017/18 summer Safeswim website

5

had long-term water

quality alerts for the following areas:

• Cox’s Bay

• Weymouth Beach

• Wairau Outlet

• Laingholm Beach

• Taumanu East

• Clarks Beach

• Meola Reef

• Little Oneroa Lagoon

• Piha Lagoon

• Wood Bay

• Green Bay

• Titirangi Beach

• Piha North Lagoon

• Fosters Bay

• Bethells Lagoon

• Armour Bay

DNA testing revealed human faecal matter was a contributing source to E. coli in the water. Failing

OSWW systems are a potential cause for this contamination.

Areas during the 2017/18 summer where council’s water quality monitoring showed hazards from

human faecal contamination are listed below:

As water quality monitoring is limited in the region, many coastal settlement areas with large

numbers of OSWW systems, such as Leigh, Whenuapai and Sandspit are not monitored.

5

https://www.safeswim.org.nz/

• Piha Lagoon

(Waitakere)

• North Piha Lagoon

(Waitakere)

• Foster Bay (Huia)

• Little Oneroa Lagoon

(Waiheke)

• Bethells (Te Henga)

Lagoon (Waitakere)

Review of On-site Wastewater Bylaws

12

4.3 Call centre complaints and queries identify OSWW failure

There is no central location where council tracks all communications from Aucklanders regarding

OSWW issues. The following lists from Licensing & Regulatory Compliance and Customer

Services provide a snapshot of communications received regarding OSWW systems.

Table 2 - Licensing & Regulatory Compliance OSWW customer communications

Table 3 - Customer Experiences OSWW customer communications

Customer Communications

Licensing & Regulatory Compliance, Environmental Health, July 2017- November 2017

• 38 people – complained about smelly systems, overflow, and leaks onto neighbouring

properties

• 35 people – needed maintenance and pump out, tank alarm going off

• 21 people – had questions about septic tanks (how to get emptied, replaced or apply for a

resource consent)

• 3 people – had formal complaints about septic tanks in general or on the cost of resource

consent renewal

Customer Communications

Customer Experiences, Customer Services, September 2016 – March 2018

• 9 calls – complained about pump out (either council contractor did a poor job, showed up

unannounced, or left the site a mess)

• 4 calls – complained about neighbour’s leaking OSWW systems and council not doing

anything about it

• 2 calls – complained about resource consents being confusing and costly

• 1 call – queried on incentives for OSWW systems

• 1 call – complemented a pump out well done

13

5 Are the bylaws still the most appropriate means for

managing OSWW systems?

To assess if the bylaws are the most appropriate means for addressing OSWW management, the

topic is broken down into three sections. The first section identifies if the bylaws supplement the

existing plans and legislation, the second explores if the bylaws have more enforcement power

than existing legislation, and the third section identifies the views of council’s OSWW stakeholders.

5.1 Do the bylaws provide extra regulation than the Auckland Unitary

Plan and legislation?

The Auckland Unitary Plan, Resource Management Act 1991, Building Act 2004, and Health Act

1956 provide rules to cover all aspects of OSWW regulation including design, installation,

operation and maintenance. These legislations also have powers of enforcement including the

ability to inspect systems, issue infringements, serve notices to stop and/or remedy, recover costs

and prosecute.

Staff conducted a comparison analysis to identify any gaps or areas in the OSWW legacy bylaws

not covered in the Unitary Plan or Acts. Out of the 55 clauses in the OSWW legacy bylaws, only

three have requirements not included in the Auckland Unitary Plan, Resource Management Act

1991, Building Act 2004 or Health Act 1956.

See Appendix 7.4 for a line by line breakdown of the legacy bylaws and where in the Auckland

Unitary Plan or Acts the stipulations are matched. Provisions in the OSWW legacy bylaws which

are not stipulated by the Auckland Unitary Plan or Acts are listed in the following table.

Key findings

• The legacy bylaws only provide an additional stipulation by requiring OSWW users to send

in their maintenance records proactively to council or when asked.

• The Auckland Unitary Plan already regulates record keeping by requiring OSWW

maintenance records to be kept on site for inspection.

Review of On-site Wastewater Bylaws

14

Table 4 - OSWW bylaw provisions not stipulated by the Auckland Unitary Plan or Acts

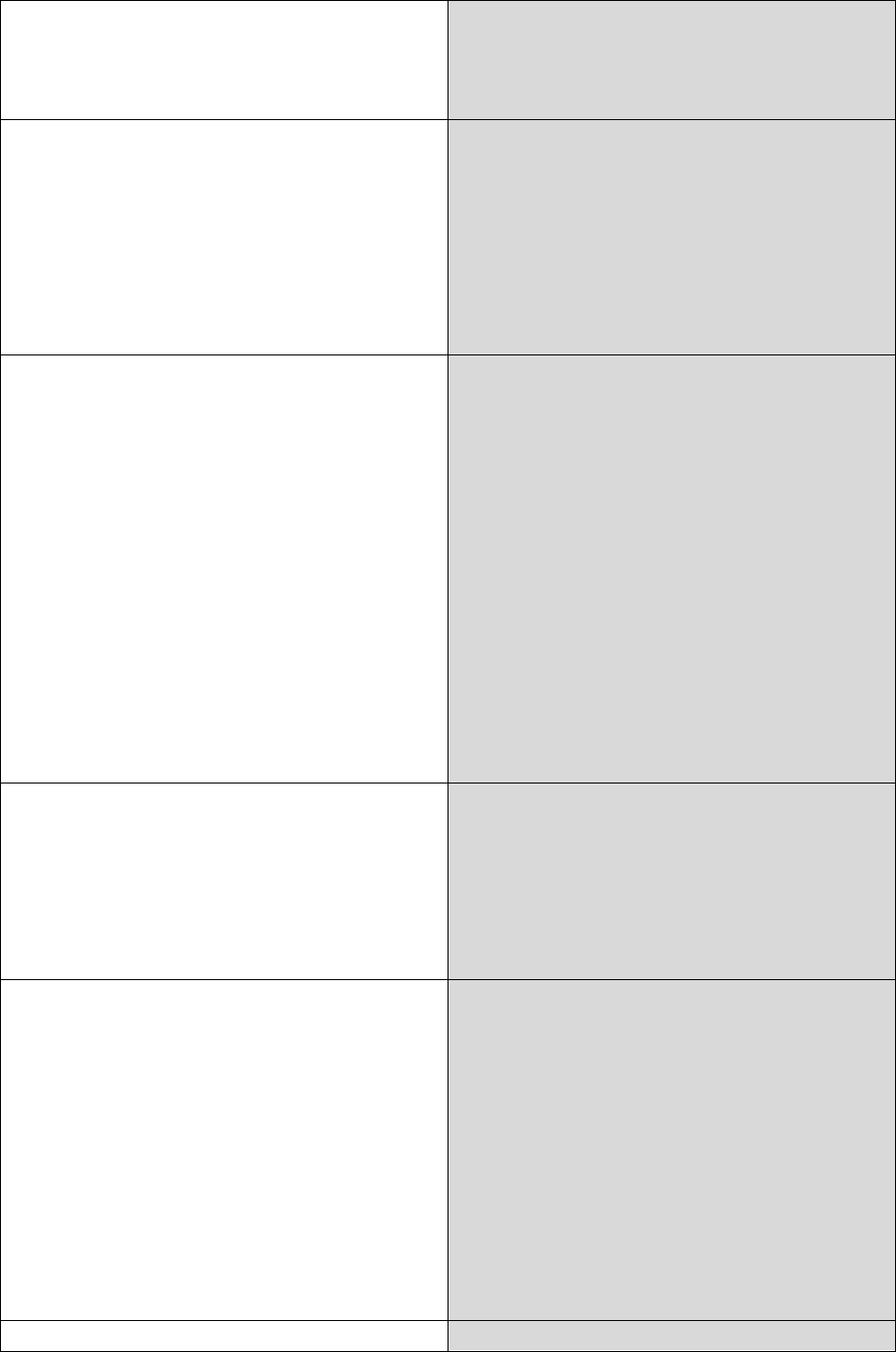

5.2 Do the bylaws provide greater enforcement power than existing

legislation?

The various acts regulating OSWW management have an array of legislative powers available for

enforcement. The legacy bylaws, created under the Local Government Act 2002, have the least

amount of enforcement power as they have no power to issue infringement notices. This limitation

means fines can only be issued on conviction.

The Resource Management Act 1991 and Building Act 2004 provide more options and range of

fines including the ability to issue on-spot fines, serve abatement notices and issue large fines on

conviction. See Table 2 on the next page for a comparison on the enforcement powers of each

legislation.

OSWW bylaw provisions not stipulated by the

Auckland Unitary Plan, Resource Manage Act 1991, Building Act 2004 or Health Act 1956

Waiheke Wastewater 2008 Section 29.5.3 – after pump out the property owner shall provide a

copy of the receipt for having this work done to the Waiheke Service Centre of the Auckland City

Council within 14 days of the tank being pumped out

Papakura District Council Wastewater Bylaw 2008 Section 13.3 – the property owner shall

provide a copy of the receipt for having this work done to Papakura District Council within 14 days

of the tank being pumped out

Rodney District Council 1998 Section 9.3 - The owner or occupier of an allotment utilising

on-site a wastewater treatment or disposal system shall, within 10 working days of receipt of

written request from an Authorised Officer provide the following information:

a. the make and model of on-site treatment installed, if known; and

b. a copy of any manufacturers maintenance and operation requirements and

performance standards; and

c. evidence, to the satisfaction of the officer, that an effective operation and maintenance

programme for the system is in place.

15

Table 5 - Enforcement powers of legislation

Powers

Act

Officers can

inspect

property

Officers can enter

dwelling house

Infringement offence and

fee (aka ‘instant fine’)

process available

Notice to stop and/or

require action to remedy

(immediate action by

enforcement officers)

Recover costs of

remedying

Prosecution through courts

and penalties on conviction

Local

Government

Act 2002

(bylaws)

(LGA s171)

Can send letters

to those in

breach, but the

legal process associated

with an abatement notice is

not triggered

(LGA s176)

Fine on conviction of up to

$20,000

Resource

Management

Act 1991

(RMA s334)

Only if

suspected

offence is punishable by

imprisonment

(RMA s338)

Up to $750

Resource

Management (Infringement

Offences) Regulations,

Schedule 1

(RMA s322)

(RMA s323)

Fine on conviction up to

$300,000 fine or 2 years

imprisonment

Health Act

1956

(HA s128)

(HA s34)

(HA s34)

If no penalty provided, liable

on conviction to a fine up to

$500 and $50 every day

offence continues

Building Act

2004

(BA s222)

If no consent

from occupier,

the District Court may

authorise officer to enter

dwelling house

BA s168(1)

$1,000 for failing

to comply with a

notice requiring work or a

notice to fix (Infringement

Offences Regulations -

schedule 1).

(BA s129)

(BA s221)

Fine on conviction up to

$200,000 and not exceeding

$20,000 for every day offence

continues

16

5.3 Do council’s OSWW stakeholders identify any additional issues a

bylaw could address?

5.3.1 Auckland Unitary Plan views

Auckland Unitary Plan regulation staff provided advice for the OSWW bylaw review in August 2017

to help staff understand the regulatory framework.

Themes

The Unitary Plan is the more appropriate tool: Council has determined that the most effective

way of controlling the design standards of new wastewater systems is through compliance with the

Auckland Unitary Plan.

Although the requirements for a bylaw change would have an easier consultation and appeal

process than a plan change, it would not be appropriate to create a bylaw just to avoid a more

stringent and time-consuming consultation process.

Licensing/permitting scheme: A bylaw can be used to supplement Auckland Unitary Plan rules,

where the proposed requirements do not fit as easily into a Resource Management Act 1991

context, i.e. a licensing/permitting scheme.

Unitary Plan standards could require an OSWW central database: While the Auckland Unitary

Plan currently does not require a list of all septic tanks to be compiled, this could be achieved by

way of an additional Auckland Unitary Plan standard that requires existing and proposed tanks be

‘registered’. However, given that this is a city-wide rule, thought would have to be given as to

whether the cost of maintaining those records would be proportionate to the benefit of holding that

information.

There is already an obligation to keep records of maintenance and allow council officers to inspect

those records in the Auckland Unitary Plan. Therefore, added benefit of requiring records sent to

council proactively may be minimal.

Key findings from Auckland Unitary Plan

• A plan change of the Unitary Plan, not a bylaw, is the appropriate mechanism to use if

changes to OSWW regulation are required.

• A bylaw could serve a purpose if a council licensing scheme for OSWW systems is

developed.

• Current legislative enforcement powers are sufficient for managing OSWW systems.

• A bylaw would not regulate anything above the current requirements in the Unitary Plan.

17

Enforcement powers are sufficient: The Resource Management Act 1991 and Auckland Unitary

Plan provisions cover all eventualities, and this is a matter of making use of council’s enforcement

powers. The bylaws would not cover anything that is not already addressed by the consenting and

permitted activity regime.

5.3.2 Local board views

Local boards were provided with a presentation on the current state of OSWW management and

the legacy OSWW bylaw review at the Local Board Chairs’ Forum in December 2017. During the

forum, six local boards requested individual workshops:

As requested, staff held informal workshops with each of the above local boards. They were

presented an overview of the current state of Auckland’s OSWW systems and given an in depth

look at the current OSWW regulatory framework. Local board members were asked questions

regarding issues with OSWW management, how it could be improved, and specifically on their

views if additional regulatory powers were needed. Themes identified from the workshops are

listed below with a complete breakdown in Appendix 7.2.

Themes

More education is required (Rodney, Great Barrier, Upper Harbour): Increased education is

needed around the existing legislation as many are unaware of their obligations to manage their

own systems. People move out into rural areas and don’t know they even have an OSWW system.

Education is needed regarding change of use, i.e. holiday home becoming permanent, and how

that effects system stress. Education design also needs to include foreign buyers.

• Rodney

• Great Barrier

• Waitakere

• Waiheke

• Franklin

• Upper Harbour

Key findings from local board engagement

• Current rules and regulations need to be simplified and communicated to OSWW users.

• Council needs a better understanding of the scale of OSWW systems’ effect on Auckland.

This could be achieved through developing a central database of OSWW systems and

increased environmental monitoring.

• Council should consider incentives as some owners cannot afford to maintain their OSWW

systems.

• No extra regulatory tools are needed. Council needs to utilise the enforcement powers

already available.

18

A central database is needed (Upper Harbour, Franklin, Waiheke, Rodney): Having all Auckland

OSWW systems in a central database is crucial for regulating, identifying problem areas and

reaching out to owners with education and correspondence.

Cost Issues are a barrier for compliance (Great Barrier, Waiheke, Franklin): OSWW

maintenance and management is a “crippling” cost and burden for some people. Some residents

are hesitant to report their OSWW failures for fear they cannot afford remedying. Getting costs

down for OSWW owners needs to be a focus. Reducing costs could be achieved by providing

incentives for upgrading OSWW systems or allowing suitable alternative systems

6

. There needs to

be long-term thinking, so owners don’t get double charged for having to install and manage an

OSWW system and then be required to connect to reticulation when it arrives. Resource consents

are expensive, specifically the water testing compliance aspect.

Need for greater enforcement (Franklin, Waiheke, Rodney): There is currently no sense of

urgency to comply with the regulations for some owners. There is a need for council to focus on

compliance and the power to enforce the standards already in place. However, a risk exists using

heavy enforcement as the reticulated system fails as well.

More environmental monitoring (Waitakere, Franklin): More monitoring and testing is needed to

understand the scale of contamination. Methods are needed to trace back to source pollution.

Miscellaneous themes: - Other themes included; creating incentives for owners to connect to

local OSWW networks, having stricter rules for sensitive environments, making sure old systems

are being captured, and providing an easy way to have pump outs extended beyond 3 years if low

use.

Waiheke Local Board’s view that the Auckland Unitary Plan would replace the Waiheke

Bylaw

Review of Waiheke Wastewater Bylaw, April 2014

Planning Policies and Bylaws reviewed the Waiheke OSWW bylaw in April 2014. The bylaw was

reviewed after administrative staff requested a bylaw amendment requiring regular inspection of

advanced systems (now a Unitary Plan rule). The Waiheke Local Board decided

7

to:

• “consider the development of a new bylaw dealing with the maintenance and inspection of

existing domestic-type on-site wastewater treatment and disposal systems

• support that the new bylaw should remain in place until suitable replacement Unitary Plan

provisions become operative.”

The Waiheke Local Board’s decision reaffirms how the legacy OSWW bylaws were only intended

to remain in place until the Auckland Unitary Plan OSWW provisions became operative.

6

Alternative systems to the traditional septic tank and disposal field include water free systems,

vermicomposting, peat filtration and incineration.

7

Waiheke Local Board, Resolution number WHK/2014/112

19

5.3.3 Enforcement officer views

To understand how the regulatory framework is practiced and enforced within council, officers from

Resource Consents, Building Consents, and Licensing & Regulatory Compliance were interviewed

from November to March 2018. The focus areas of these interviews included how the management

process works, what issues exist, and what could be improved. The key themes are listed below

with the full breakdown in Appendix 7.3.

Interviewees

• Resource Consents – Senior Specialist, Natural Resources and Specialist Input

• Resource Consents – Principal Specialist, Wastewater and Coastal Team

• Licensing & Regulatory Compliance – Senior Specialist, Targeted Initiatives

• Licensing & Regulatory Compliance – Team Leader, Environmental Health

• Licensing & Regulatory Compliance – Waiheke’s Compliance Monitoring Officer

• Building Consents – Building Surveyor, Field Surveying

Themes

Simplicity of OSWW rules is needed: Owners have confusion and a “very apparent lack of

education” on responsibilities for managing OSWW system. The process and rules need

simplifying, so they can be easily communicated to owners. The permitted activities in the Unitary

Plan should be more black and white, especially regarding maintenance. Council receives a lot of

questions relating to needing maintenance and pump out. There is an expectation that the council

maintains all OSWW systems across Auckland.

Key findings from interviews with enforcement officers

• Many OSWW owners think council is responsible for maintaining their systems; there

needs to be increased awareness and education of the rules and regulations.

• Council responds only if there is already a problem. Relationships can be forged with

pump out contractors to alert council to impending issues.

• The enforcement powers in the Acts are sufficient, and officers will normally utilise

alternative methods, such as notices and warnings, before applying the full force of the

law.

• The building consent process should include a cumulative look at who else has OSWW

systems in the area and restrict landscaping of those with soakage fields.

20

The Auckland Unitary Plan is not easy to decipher for council officers as well. Wording of E5.6.2.2

is not helpful regarding what was considered a permitted activity without the need for a resource

consent when the Unitary Plan became operative.

Some Aucklanders have chosen to install alternative systems, but it is not an easy process as the

consenting process for alternative systems is quite convoluted.

Council is only reactive: A Unitary Plan breach is only triggered when an adverse effect

happens. Overloaded systems often need a blatant failure before it’s identified as a problem.

A temporary fix is not a solution: When a complaint is made and investigated, sometimes the

immediate nuisance is addressed (smell) but not the underlying problem (overuse).

Relationship with pump out contractors is important: Council sometimes get calls from service

and maintenance providers reporting that some of their customers are no longer maintaining their

systems and council should respond. However, council does not have the resources to address.

There have been stronger proactive arrangements in the past where after pump outs, contractors

would send a copy of the report to council. Where issues were noted with the tank, these would be

recorded, and a letter sent out to the owner to advise them of the possible defect.

Officers give warning first, enforce second: Current officer preference is to negotiate with the

landowner before using the force of law. Enforcement is not common due to the issue of increasing

negative public perception and cost. It is costly for council to prosecute, and the perpetrator often

can’t afford their own OSWW system let alone legal fees. Most often, warnings are provided for it

to be fixed. If no compliance, abatement can be considered. Council needs to be prepared to

enforce the notices and charge the customer. Compliance with notices is quite good as people

have a self-interest in fixing the issue.

Cumulative effect is an issue: The OSWW building consent application is assessed in isolation.

There is no neighbourhood or environmental scan completed to determine what impact a new

system will face, and problems arise with the cumulative strain of soakage fields. Soakage fields

can also be disrupted by minor landscaping which do not require a resource consent, such as

recontouring or adding a retaining wall. This change becomes a problem when one or more

property owners landscape and the cumulative impact inadvertently effects other’s soakage fields.

There are issues with the Code Compliance Certificate: There is no legal requirement for Code

Compliance Certificate (CCC). In practice, two years after a building consent is granted, an internal

decision is made whether to grant a CCC. If not granted, the homeowner would need to apply for

one later. The CCC issue would generally arise only when the property is sold, and a Land

Information Memorandum report is obtained. There is a gap in the Building Act 2004 as there are a

lot of OSWW systems without a CCC, and there is no ability to test those systems where no CCC

is issued. Officers assume this is a significant issue in rural areas.

Warrant of Fitness scheme would have risk: If council was involved with the certification

process, consideration needs to be given to council’s increased liability and legal risk if there is a

subsequent failure or issue. With more oversight and control comes more responsibility and

liability.

21

Rules are needed for upgrading OSWW systems: there is currently no requirement in the

legislation to upgrade OSWW systems.

Maintenance agreements not building consent law: Maintenance agreements are not legally

required for obtaining a building consent. Council’s consent process asks for a maintenance

agreement, but applicants can push back. And if they do enter one, there is nothing stopping them

from cancelling right after. However, the Unitary Plan requires regular maintenance once

operational.

Note: A bylaw cannot provide solutions to building consent issues.

A bylaw could not address problems regarding the cumulative effect of OSWW soakage fields or

the Code Compliance Certificate as a bylaw can not provide criteria additional or more restrictive

than the existing building code. Changes would need to be made to council’s building consent

process or to Auckland’s Building Code.

5.3.4 Waiheke’s Compliance Monitoring Officer interview

Requiring OSWW users to send in their pump out records proactively to council is the main

additional component the legacy bylaws provide over the Unitary Plan, Building Act 2004 and

Health Act 1956. The legacy bylaws enable this power for Papakura and Waiheke, although

Papakura does not utilise this feature.

To understand the benefits and issues of requiring proactive reporting, Waiheke’s Compliance

Monitoring Officer in Licensing and Regulatory Compliance was interviewed in March 2018.

Themes

Proactive reporting works well: The reporting scheme on maintenance and pump out generally

works well on Waiheke. Operators are also sending in advanced treatment systems maintenance

although not required.

Most residents comply:

Very few people do not comply with sending in records of pump out. A

letter is sent out reminding people of their obligations and advises about the bylaw which generally

gets good compliance. However, when people do not comply, no follow ups occur. Residents are

Key findings from Waiheke’s Compliance Monitoring Officer

• Building relationships with OSWW operators and maintenance providers is crucial to an

effective maintenance reporting scheme. The bylaw assists, but it is not required for

having records sent to council.

• Council messaging for requiring records needs to reflect it is in the owner’s interest to

maintain their systems to avoid failure and subsequent costs.

22

not always happy about this requirement, but they comply as it is in the owner’s interest to maintain

or pump out their systems to avoid OSWW failure and subsequent costs.

More education is needed:

Waiheke needs education for owners regarding OSWW

management. New owners find out about septic systems with a Waiheke welcome pack.

Building relationships with OSWW service providers is crucial:

There are only a few OSWW

maintenance providers on the island, so it is easy to foster relationships. The Waiheke bylaw

doesn’t require advanced treatment maintenance records to be sent to council, but the reporting

occurs because of the relationships forged with the commercial operators. When doing

inspections for failures, staff will work with the owners to help fix the issue instead of issuing fines

as it’s more effective. Have only had to issue an abatement notice once in ten years.

Advanced systems are failing the most:

Septic tanks are common on the island due to age of

buildings. New dwellings can be large for their section leaving smaller area for a disposal field and

at a higher use. Failings come most from advanced systems as they require more maintenance.

Note:

Although most residents comply with the proactive reporting scheme on Waiheke, there are

still issues with OSWW failure on Waiheke as seen by long-term hazards in Little Oneroa Lagoon.

5.3.5 Healthy Waters’ review of OSWW management

The Environment, Climate Change and Natural Heritage Committee

8

commissioned the creation of

a cross-council group in March 2016 to develop options for better management of privately-owned

OSWW systems. The group was also tasked to compare costs and benefits and recommend a

preferred solution to be ready for consideration during the 2018-2028 Long Term Plan process.

Healthy Waters has led this project group, and the current OSWW system bylaw review

contributes. The proposed OSWW Long Term Plan for development of a regulatory framework set

forth by Healthy Waters proposes the following from 2018-2023:

• enactment of regulation, including public consultation

• creation of a region-wide OSWW database

• establishment of a targeted rate or licensing administration

• set up of a certification scheme for maintenance contractors

• roll out of Guidance Document 06 (GD06) to update Technical Publication 58 (TP58)

• review and update education materials

• develop a monitoring programme for high risk areas as model validation.

After 2023, plans include a roll out of education initiatives, recruitment and training of additional

compliance officers, and a monitoring programme.

Note: None of the activities identified in Healthy Water’s proposal above are dependant or a

contingent to the council having a bylaw.

8

Environment, Climate Change and Natural Heritage Committee, Resolution Number ENV/2016/7

23

6 Statutory review findings and conclusion

The Local Government Act 2002 requires that the OSWW bylaws are reviewed by October 2020.

The review must comply with statutory requirements under the Act by identifying if the bylaws are

the most appropriate means for regulating OSWW systems.

In summary, the research and engagement contained in this report found the following.

The issues the bylaws set out to address are still problems

OSWW systems are failing across Auckland as seen from data showing unhealthy amounts of

human sourced E. coli in Auckland’s recreational water in addition to call centre complaints of

malfunctioning systems.

A bylaw is not the most appropriate means for addressing OSWW management

The findings show there is currently no regulatory gap for OSWW management which a bylaw

could address. The legacy OSWW bylaws provide no extra regulations to those already available

in the Auckland Unitary Plan, Resource Management Act 1991, Building Act 2004 and Health Act

1956.

Although the Waiheke and Papakura bylaws require users to send maintenance records to council,

this can be achieved without a bylaw through effective communication with the community and

relationship building. Council also can inspect the maintenance records on-site as stipulated in the

Auckland Unitary Plan.

If a change to regulation was required, it would need to be achieved through a plan change of the

Auckland Unitary Plan. The Auckland Unitary Plan was meant to replace the legacy OSWW bylaws

as the guiding document for managing OSWW systems.

There are non-regulatory opportunities

Most of the issues identified through the regulatory gap analysis and engagement had more

appropriate options to address the problem than a bylaw or law change such as:

• increasing the education of OSWW rules and regulations

• simplifying the OSWW regulations for communication

• increasing the understanding of the scale of OSWW system’s effect through a central

database of OSWW systems and increased environmental monitoring

• providing cost incentives for users to upgrade and/or maintain systems

• undertaking proactive OSWW risk of failure identification through relationship building with

OSWW service providers

• using the enforcement tools available in the Auckland Unitary Plan, Resource

Management Act 1991, Building Act 2004 and Health Act 1956.

24

7 Appendix

7.1 Estimate of OSWW location and scale

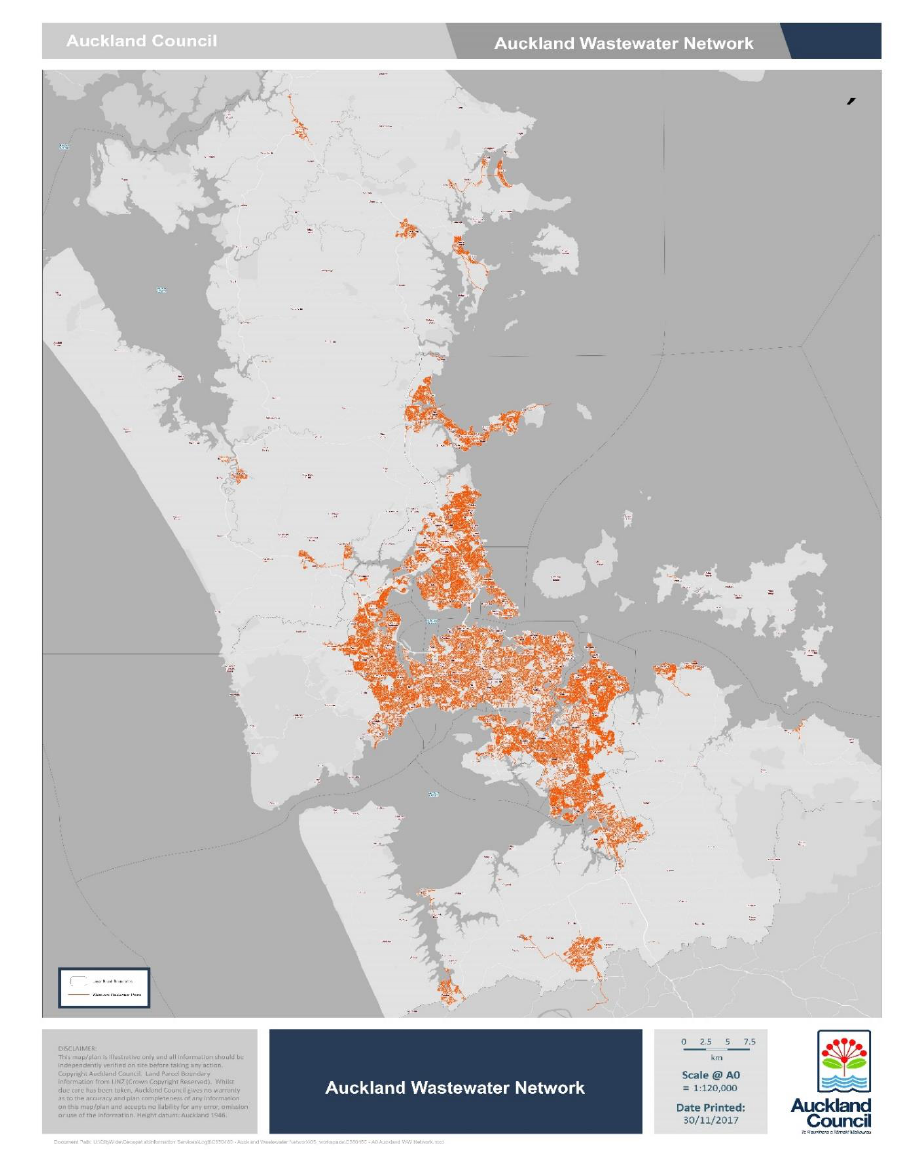

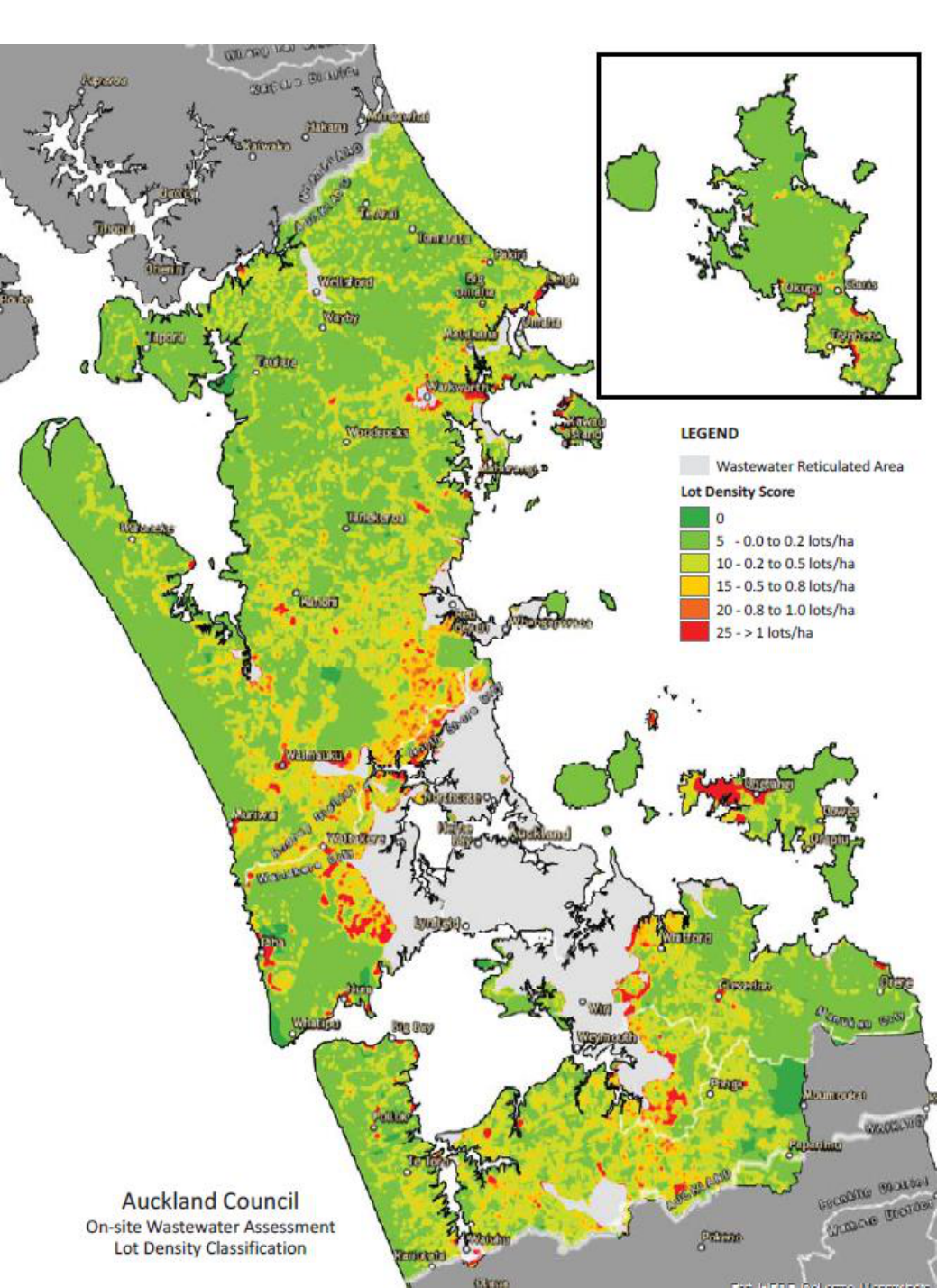

The 50,000-60,000 OSWW system estimate across Auckland came from analysing the two maps

below. The first map shows Watercare’s wastewater network. With the assumption that those not

on reticulation have an OSWW system, the lot density is overlaid on areas without reticulation in

the second map to give an estimate of amount of OSWW systems.

Figure 2 - Watercare wastewater network

25

Figure 3 - Lot density over non-reticulated areas

26

7.2 Local board views table

Table 6 - Local Board Views

Rodney

• Education - Unawareness around existing legislation and bylaws, there

needs to be more education of what’s already in place. People move out into

rural areas and don’t know they even have an OSWW system.

• Central database for OSWW systems

• Change of use – when someone applies for a new OSWW system or buys

a new property, it should kick off investigation of what systems are already on

the property. The new owners should be educated on OSWW systems as

well.

• Enforcement issue

• Incentives – should be incentives to connect to local OSWW network

Great

Barrier

• Enough legislation - There is already extensive legislation in the

RMA/BA/HA, maybe even too much, and any additional bylaws would be

over the top. The community would not appreciate council inspecting their

maintenance records on-site. There are no additional powers needed than

already set out in the existing legislation

• Education – most residents unaware of the existing legislation

• Cost Issue - OSWW maintenance and management is seen as a crippling

cost and burden for the Great Barrier demographics. Residents hesitant to

report their OSWW failures as fearful won’t be able to fix it. Needs to be

focus on getting costs down for OSWW owners and allowing alternative

systems or helping people upgrade their systems.

Waitakere

• Environmental Monitoring – find a way to trace point source pollution

• Pump-out – make sure pump-out contractors are reporting back issues they

find. And make sure pump-outs are only occurring when needed instead of

by the clock. Too frequent pump-outs can compromise effectiveness of low

volume systems and less foot track needed as there is a risk of spreading

Kauri dieback.

• Targeted rate - concerned over value of targeted rate for pump-out as

compared to using a private pump-out provider

27

• Proposed water levy – concern the funds would be unfairly used on the

inner city

• Stricter rules for sensitive environments

• Power of entry and inspection – make sure this power remains available

as key to identifying pollution sources

Waiheke

• Simplicity – need a regulatory framework that is easy for people to access

and highlights problems and how to deal with them

• Cost issue - need to consider unintended consequences and additional

costs for Aucklanders. Outcomes thinking is required as opposed to outputs.

• Enforcement – focus on compliance and the power to enforce standards in

place. There is currently no sense of urgency to comply.

• Central database for OSWW systems

• Better OSWW testing – currently there is a crudeness of testing.

Mechanisms to improve quality of testing and determining failure cause are

needed.

• Old systems are an issue – old concrete block septic tanks that have little

maintenance on them. Little Oneroa has oldest houses.

• Change of use – Waiheke specifically has issues with change of use from

holiday visitors and permanent accommodations.

Franklin

•

Pump-out frequency

– three yearly pump-out timeframe not best measure,

instead should be based on the system.

•

Old systems

- make sure regulations apply to old systems from the 30s and

40s as well

•

Resource issue

- it’s a big job for compliance officers to inspect and go to

each system in rural areas.

•

Central database for OSWW systems

•

Incentives –

how can we enable users to connect to shared system

•

Cost –

what is fair and equitable to get people to upgrade their systems.

Don’t double charge people for forcing them to manage OSWW system and

28

then connect to reticulation when it arrives. Concern over resource consents

being expensive, specifically the water testing compliance aspect.

•

Cumulative effects

– concern over multiple systems together

•

Environmental Monitoring

– more monitoring and testing needed,

especially DNA testing

•

Enforcement

- would like to see council be careful about taking a heavy

hand to enforcement given the reticulated system fails as well. Consider the

practical effects of enforcement and what can actually be achieved going in

heavy.

Upper

Harbour

• Education – including foreign buyers

• Central database for OSWW systems

• No overregulation – those who maintain their systems properly shouldn’t be

punished because of those who don’t. Big waste of council resource to try

and maintain all OSWW systems, should just deal with problems.

• Intensification issue – paddocks have been divided for new subdivisions,

cutting through septic lines

29

7.3 Council enforcement officer views table

Table 7 - Council enforcement officer views

Dec 2017

Resource

Consents –

Natural

Resources

and Specialist

Input – Senior

Specialist

Resource

Consents –

Principal

Specialist

wastewater

and coastal

team

Licensing and

Regulatory

Compliance –

Senior

Specialist

• No additional legislation needed - Licensing and Compliance have all

the tools. The Unitary Plan advises when an OSWW system is a

permitted activity. When there is an adverse effect, can provide an

abatement notice.

• Simplicity needed - The process and rules need simplicity so can be

communicated to what owners must do. The permitted activities in the

Unitary Plan should be more black and white, especially regarding

maintenance.

• Resource consents – currently have a low number of OSWW systems

which have resource consents, approx. 2,000. These are kept on record

and are monitored and have requirements as part of their resource

consent. A risk profile is allocated, and reporting is required on a

frequency related to risk.

• Process for Unitary Plan breach – generally, permitted activities are

low risk. They would need complaints to be made adverse effects before

triggering the system:

o A complaint is needed

o Evidence that maintenance requirements are not being met.

Unitary Plan E6.1.1(3) could be used as all very effects based.

o If found to be a breach, would do a risk-based assessment on the

effect on the environment, how long the breach has been

occurring, the attitude of the owner/occupier in taking steps to

remedy the breach

o Most often, warnings would be provided for it to be fixed. If no

compliance, abatement can be considered

o If not fixed, can require a resource consent so it will be a

complying activity. Advantage here is the monitoring built into

resource consents and can hold people accountable. It is a

mechanism to go out and check compliance with maintenance

requirements.

• Issues:

o When a complaint is made and investigated, the immediate

nuisance is addressed (smell) but not the underlying problem

(overuse)

30

o Overloaded systems often need a blatant failure with adverse

effects to occur before it’s identified as a problem

o Unitary Plan wording of E5.6.2.2 is not helpful regarding what was

considered a permitted activity with a resource consent when the

Unitary Plan became operative

o There is no requirement in the RMA or other legislation to

upgrade OSWW systems

o Council sometimes get calls from service and maintenance

providers reporting that some of their customers are no longer

maintaining their systems and council should do something. But

council doesn’t have the resources to address.

o Council very reactive

• Warrant of fitness - If council was involved with the certification process,

need to consider council’s increased liability and legal risk if there is a

subsequent failure or issue. With more oversight and control comes more

responsibility and liability.

Nov 2017

Building

Consents,

Building

Surveyor

• OSWW in bad situation – cannot make OSWW systems compliant

under the current regime. The environmental standards are impossible to

reach, there is an issue with creating site surveys and fields which

comply with TP58 and OSWW systems are overused in the summertime

months (e.g. Muriwai).

• Issues:

o The building consent application is assessed in isolation (only the

subject property or in rare circumstances of an encroachment, the

subject properties will be assessed). There is no neighbourhood

or environmental scan completed to determine what is happening

in the area and whether that would impact on any system being

put in.

o No legal requirement for Code Compliance Certificate. In practice,

two years after a building consent is granted, an internal decision

is made whether to grant a CCC. If not granted, the homeowner

would need to apply for one later. A letter would be sent out to

those people who fall into that category. The CCC issue would

generally arise only when the property is sold, and a LIM report is

obtained. There is also a gap in the Building Act that there are a

lot of plants without a CCC and no ability to test those systems

where no CCC is issued. It is assumed that this is a significant

issue in rural areas.

31

o Even if CCC issued, problems can arise. Soakage fields can be

disrupted by minor landscaping which don’t require a resource

consent such as recontouring or adding a retaining wall. Can also

be affected by cumulative effect where one or more property

owners landscape inadvertently effecting other’s soakage fields.

o There is no legal requirement for a maintenance agreement to be

entered to obtain a building consent. Council’s building consent

process asks for a maintenance agreement, but applicants can

push back on this. And then if they do enter one, there’s nothing

stopping them from cancelling right after.

o If the system is not working or not functioning correctly and there

have been no changes to it, it is still technically compliant with the

Building Code. This situation is difficult. Estimates 90% of old

systems not operating properly.

• Pump-out contractors - When pump-out contractors notice an issue and

report to council, there is the ability under the Building Act to declare a

building as insanitary on the basis that there are no working sanitary

features/facilities. That is the strongest tool they have in the Building Act.

It requires an insanitary building notice to be issued. If there is no

compliance with the notice, the council can infringe straight away with a

$2,000.00 fine or prosecute. The notice can also require emergency

work is completed (minimum timeframe is 10 days). The argument is that

the pipes are part of the building elements. No challenge has been raised

to these notices yet, however this is untested.

• Alternative OSWW systems - Needs to be a better definition for OSWW

systems. There are alternative waterless systems involving composting.

Some Aucklanders have chosen to install these alternative systems, but it

is not an easy process as the consenting process for alternative systems

is quite convoluted

• Enforcement - Council needs to be prepared to enforce the notices –

enforcement is not common due to the issue of public perception and

cost – both cost to council and the issue of getting funds out of someone

who cannot afford to pay for the system in the first place.

November

2017

• Customer queries on maintenance - Receive a lot of questions relating

to maintenance of the systems and those trying to get an early pump out.

There is an expectation that the council maintains all OSWW systems.

Often those complaints are dealt with quickly and they are told to get a

private provider involved as the council does not provide maintenance.

32

Licensing and

regulatory

compliance –

environmental

health – team

leader

Receive about two complaints a week, mostly about who is maintaining

their system.

• Unitary Plan communication not effective - have found no change in

enforcement since the Unitary Plan came into force

• Health Act 1956 - When issues arise which require resolution by their

team, e.g. causing nuisance with smell or foul water, they utilise the

powers under the Health Act. most people will fix the issue once a

nuisance notice has been served on them. Within the nuisance notice,

they would have a reasonable timeframe to make the necessary repairs.

If there has not been compliance, or if there is urgency, council can go in

and arrange for it to be fixed, with the cost then charged to the

customer/property owner. This does not happen often. In determining

whether to go down the path of the council arranging for it to be fixed and

on charging the customer, a risk assessment would be completed. This

would include determining the level of contamination, whether there were

vulnerable people at the site and the response from the property owner.

They are reluctant to do a charging order and would prefer to negotiate

with the landowner. While the negotiation process does involve a lot of

work for them, it is the preference.

• Resource Management Act 1991 – no RMA tools are used by this team

to enforce or deal with issues or breaches

• Customer compliance - compliance with the notices is quite good as

people have an interest in fixing the issue as it affects them personally.

Where problems arise are with tenanted properties where the landlord is

uncontactable, or not interested in fixing it.

• Pump-out contractors reporting - Previously, when the contractor

completed pump outs, they would send a copy of the report to council.

Where issues were noted with the tank, these would be recorded, and a

letter sent out to the owner to advise them of the possible defect. This

was sort of a proactive arrangement whereby it would act like an informal

inspection taking place as part of the pump out scheme and repairs could

be affected before there was a failure of the system.

• Issues:

o Very apparent lack of education and confusion about

responsibilities

o Locating systems on the properties can be difficult, especially old

as-built plans being inaccurate or unavailable. Information is

incomplete and inaccurate

o Issue with change of use and the system not coping. Especially in

areas like Piha where there has been a change of the property

from a bach to permanent residence.

33

7.4 OSWW bylaw provisions compared to Resource Management Act

1991, Building Act 2004 and Health Act 1956

Table 8 - Auckland City Council Bylaws: Bylaw No. 29 - Waiheke Wastewater 2008

Bylaw Stipulation

Matching stipulation in Resource

Management Act 1991, Building Act 2004

and Health Act 1956

On-site disposal

29.1.1 All wastewater generated on an

allotment shall be disposed of within the

confines of that allotment unless otherwise

approved by the Council and the Auckland

Regional Council.

Health Act s39 requires all dwellings to have

suitable appliances for the disposal of refuse

water in a sanitary manner.

Building Code G13.2(b) states if no sewer

system available, an adequate system for

the storage, treatment, and disposal of foul

water must be provided in buildings in which

sanitary appliances using water-borne waste

disposal are installed.

Building consent

29.2.1 Owners of properties who wish to

install a domestic wastewater treatment

system on their properties shall apply for a

building consent in terms of the Building Act

2004.

Building Act 40 (1) – A person must not carry

out any building work except in accordance

with a building consent.

29.2.2 A building consent application to

install a domestic wastewater treatment

system shall include such details as may be

required by the council to assess its

compliance with the Building Code, the

requirements of the Auckland Regional

Plan: Air, Land and Water, (ALWP) and the

following:

a. The procedures for the testing,

commissioning, operation and

maintenance of the system;

b. The size and contours and intended use

of the site;

c. Soil conditions including permeability

and stability;

d. Vegetative cover;

e. Ground water and surface water

conditions;

f. Location of existing and future buildings

Building Act s49 - A building consent

authority must grant a building consent if it is

satisfied on reasonable grounds that the

provisions of the building code would be met

if the building work were properly completed

in accordance with the plans and

specifications that accompanied the

application.

As part of building consent an on-site

Wastewater Disposal Site Evaluation

Investigation Checklist (known as the

Appendix E form) must be completed and

signed. Part of On-site Wastewater Systems

Design and Management Manual (TP58).

Appendix E includes:

• Performance of adjacent systems

• Estimated rainfall and seasonal

variation

34

(including water tanks), parking areas

and driveways;

g. Access for maintenance of septic tanks

and disposal areas;

h. The position of adjacent streams and

waterways;

i. A soil profile test outlining the soil types

encountered to a depth of 1.5 metres or

groundwater depth by means of a

suitably sized borehole or test pit.

The council may within the period

prescribed by the Building Act require the

owner to provide more information to

determine whether or not the domestic

wastewater treatment system will meet the

requirements of the Building Code.

The Auckland Regional Plan: Air, Land and

Water requires all domestic wastewater

treatment systems to be designed, installed

and operated in accordance with Auckland

Regional Council’s Technical Publication 58

(TP 58): On-site Wastewater Systems:

Design and Management Manual. Appendix

E of TP58 contains an on-site wastewater

disposal site evaluation investigation

checklist. Council will also have regard to

the requirements of this appendix when

assessing building consent applications to

install domestic wastewater treatment

systems.

• Vegetation cover

• Slope shape

• Slope angle

• Surface water drainage

characteristics

• Flooding potential

• Surface water separation

• Site clearances

• Site characteristics

• Site geology

• Subsoil investigation

• Assessment of environmental effects

Granting of consent

29.2.3 After considering an application for a

building consent, the council shall grant the

consent if it is satisfied on reasonable

grounds that:

a. the provisions of the Building Code

and

b. the permitted activity standards for

domestic wastewater treatment

systems in the ALWP,

would be met, if the work on the domestic

wastewater treatment system was

completed in accordance with the plans and

specifications submitted with the

application.

Building Act s49 - A building consent

authority must grant a building consent if it is

satisfied on reasonable grounds that the

provisions of the building code would be met

if the building work were properly completed

in accordance with the plans and

specifications that accompanied the

application.

35

The council may accept producer

statements from approved persons for the

design and construction of domestic

wastewater treatment systems.

Wastewater treatment systems that do not

comply with the permitted activity status in

the ALWP must be approved by the

Auckland Regional Council before the can

be installed. Once approved the installation

of the system will still require a building

consent from Auckland City Council.

As-built plans

29.2.4 The council shall not provide a code

compliance certificate for a domestic

wastewater treatment system until the owner

has provided the council with a copy of the

as-built plans of the completed installation

Building Act s92 - An owner must apply to a

building consent authority for a code

compliance certificate after all building work

to be carried out under a building consent

granted to that owner is completed.

Building Act s94 - A building consent

authority must issue a code compliance

certificate if it is satisfied, on reasonable

grounds, —

a. that the building work complies with the

building consent

Drainlayer

29.3.1The installation, alteration or repair of

all domestic wastewater treatment systems

involving septic tanks and underground

pipelines shall be undertaken by a

registered drainlayer.

Building Act s84 - All restricted building work

must be carried out or supervised by a

licensed building practitioner who is

licensed to carry out or supervise the work.

Plumbers, Gasfitters, and Drainlayers Act

2006 s10 - A person must not do any

drainlaying, or assist in doing any

drainlaying, unless that person is authorised

to do so under this section.

The following persons may do drainlaying, or

assist in doing drainlaying, within the limits

prescribed in regulations (if any):

a. a registered person who is authorised to

do, or assist in doing, the work under a

current practising licence; or

b. a person who is authorised to do, or

assist in doing, the work under a

provisional licence.

Notifying Council

Building Act 40 (1) – A person must not carry

36

29.3.2 All new domestic wastewater

treatment systems and any alterations to

existing systems shall be inspected by an

authorised officer before being covered up.

out any building work except in accordance

with a building consent.

As part of council’s consent process, Onsite

Wastewater Final Checklist requires

inspection - AC1231

Testing and commissioning

29.4.1 New domestic wastewater treatment

systems shall be tested and commissioned

according to any conditions that the council

may include in a building consent.

Building Act 40 (1) – A person must not carry

out any building work except in accordance

with a building consent.

Building Act s49 - A building consent

authority must grant a building consent if it is

satisfied on reasonable grounds that the

provisions of the building code would be met

if the building work were properly completed

in accordance with the plans and

specifications that accompanied the

application.

Maintenance

29.5.1The owner of any property which

contains a domestic wastewater treatment

system shall ensure that at all times access

is available:

a. To the treatment system or septic tank

so that it can be easily opened for the

purposes of cleaning, removal of settled

solids and maintenance;

b. To any disposal field or disposal system

so that it can be maintained in good

working order.

Building Code G13.3.1 (2) – The plumbing

system shall be constructed to provide

reasonable access for maintenance and

clearing blockages.

Building Code G13.3.2(d) – The drainage

system shall be provided with reasonable

access for maintenance and clearance

blockages.

Building Code G13.3.4 – If no sewer is

available, facilities for the storage, treatment

and disposal of foul water must be

constructed with adequate vehicle access for

collection if required and permit easy

cleaning and maintenance.

29.5.2 Domestic wastewater treatment

systems shall be maintained and operated

in such a manner to prevent any discharge

of wastewater onto the surface of any land

or into any water body.

Unitary Plan E5.4.1 permitted activities allow

discharge of treated domestic type

wastewater only.

Otherwise:

Resource Management Act s15 - No person